Hello! The very last podcast in this series.

You can listen to the podcast on the simple landing page here: https://share.transistor.fm/s/0c4117d7

You can download the mp3 here: https://media.transistor.fm/b994ac43.mp3

Transcript to the Nordic By Nature Podcast, ON NARRATIVES

Tanya Intro:

Welcome to Nordic By Nature. A podcast on ecology today, inspired by the Norwegian Philosopher Arne Naess, who coined the term Deep Ecology.

In this episode ON NARRATIVES, we hear from four people working to shape more constructive narratives of our relationship to nature in order to increase environmental protection.

First, we hear from Tom Crompton, founder of the Common Cause Foundation in the U.K. whose research into values shows that the dominant narrative of the selfishness of humankind is deeply flawed.

Then, Paul Allen from the Centre of Alternative Technology in Wales presents a positive and attainable vision of the future.

We then hear from Yuan Pan, whose work integrating biodiversity into the Natural Capital Framework at Cambridge University aims to help businesses and policy makers make smarter decisions and start understanding the direct benefits from acting as stewards of the environment and nature’s resources.

Finally, we hear from Rewilding expert Paul Jepson, who is also active in science communication, particularly in the area of nature recovery, science-policy interfaces and public participation. In 2018, Paul published two papers, one with Frans Schepers and Wouter Helmer on putting rewilding principles into practice and a second where he proposed that in Rewilding we are seeing the emergence of a new ‘Recoverable Earth’ environmental narrative. . Paul currently works for the UK-based consultancy Ecosulis Ltd.

SOUND BRIDGE

TOM CROMPTON

Tom Crompton Intro

So, my name’s Tom Crompton. I direct a small not for profit called Common Cause Foundation which works on people’s values, what matters to people, and what shapes what matters to people, and our perception of what matters to our fellow citizens.

As soon as you begin to ask that question of what it is that underpins public appetite for ambitious change, you are led the social psychology of a values, of human motivation.

So, there’s a great deal of data on people’s own values. And there’s very little data on people’s perception of their fellow citizens values.

Tom Crompton from the Common Cause Foundation.

Researching the Impact of Values

We’ve used a standard values questionnaire, the ‘Thoughts Values Survey’

So, we have used that to start to ask people about their own values and then we’ve asked them to think about a typical fellow citizen, to respond about the values that they feel that typical fellow citizen holds to be important

What we find is that with regard to people’s own values, and in line with a great deal of other existing research, we find that people tend to place particular importance on what we call ‘compassionate values’.

So, these are values of friendship and kindness and social justice and equality and honesty and probably also include values of self-direction, values of curiosity and creativity.

So, people hold those values to be very important. And they attach relatively low importance to a set of values which is psychologically stand psychological opposition to those compassionate values. We call them self-interest values, and these include values of concern for finance financial success, or public image or social status.

Around about three quarters of people attach more importance compassionate values than they do to the self-interest ones.

A Fundamental Misunderstanding

So, then when we move on to ask people about what values they feel a typical fellow citizen holds to be important, we find that there’s a widespread misunderstanding that people typically underestimate the importance that a typical fellow citizen places on those compassionate values, and overestimate the importance that they place on the self-interest values.

That doesn’t incidentally seem to be as a result of reporting bias, you might imagine that a participant is perhaps reluctant to acknowledge the importance that they place on those self-interest values, but we are able to control that and that doesn’t seem to be the case.

What we find is that the more inaccurate a person’s perception of the typical fellow citizens’ values, the less connected that person is likely to feel to their community, the less likely they are to have participated civically, recently the less likely they are to voted, and the less supportive they are for action on a range of social and environmental issues for example, homelessness or climate change or inequality, and the lower their wellbeing.

The simple truth that actually our typical fellow citizens care more about one another in the wider world than we might imagine, and we project that where we’re successful in conveying a more authentic understanding of what a typical fellow citizen or a typical person holds to be important.

Then we would anticipate that that would help to strengthen a sense of community strength and commitment to civic participation, strength and public support for action on social and environmental issues and strengthen people’s well-being.

Why Do We Think Others Are Materialistic?

I think we’ve perhaps been told for so long that we have essentially atomised self-interested individuals out to kind of optimise our own… And our outcomes… For our own selfish purposes. You know, it’s such a dominant understanding of human nature that lends right to a right to the natural sciences right to the social sciences that we’ve come to believe in.

And of course, it’s something that when we see people interacting with one another in large numbers it’s very often in a commercial environment, the kind of environment that we know tends to do more to cue or pry those more self-interested values.

So, what we’ve begun to do is to ask what kind of organisation might be able to work to convey to people a deeper appreciation of the concern of the importance that most people attach the most compassionate values.

Social Purpose driven Organisations

If an organisation and an organisation sees or identifies a sense of social purpose in deepening the feeling of community and well-being among the audiences that it engages and then I think a wide range of ways in which he can begin to communicate with those audiences in ways which will facilitate that. I think it would be simply part of it could become part of the patina of how an organisation communicates with its stakeholders.

On Greater Manchester

One area in which has been real interest in this work is in the in the city’s resilience teams have a team that is actually working to think about how the people of Greater Manchester respond to disasters. And of course, traditionally that’s work which has tended to focus on the practicalities of disaster or emergency response. But increasingly there’s recognition that the importance of working upstream that actually it’s how, um, it’s how citizens respond in an emergency. It’s the values which come to the fore in the course of those responses which is so important in shaping how, how collectively, a disaster or an emergency is met.

I think there’s also an opportunity to develop. I suppose a sensitivity to seeing where those values are already in action. And then suddenly or gently drawing attention to them. I think you know so often, we don’t recognise those values in action when we encounter them.

I think the important thing to do perhaps is to develop a sensitivity to seeing those values in action, and then creativity and imagination in thinking about how they might be made more salient, and that’s going to be different in every different organisational context.

Misperceptions from media and advertising

If you think if you think about the reverse side of it if you like. The perception, the misperception that most people are driven primarily by self-interested or selfish urges, that something which is implicit in so many of the ways in which we’re communicated at. By such a diverse range of different organisations. It’s not that that’s coordinated in any way. It’s just that it becomes so deeply embedded in our understanding of what it is that motivates one another, that those are the motivations we reach for, and tacitly connect with. In the course of communicating with people.

The question would be, the question that really interests me is and how do you move beyond the situation with people who are finding themselves to a common interest to a common concern, in the ultimate sense by seeing ourselves as human beings, we recognise that there are values of concern for one another in the wider world that are an inherent part of that identity.

SOUND BRIDGE

—————————————————————————

PAUL ALLEN

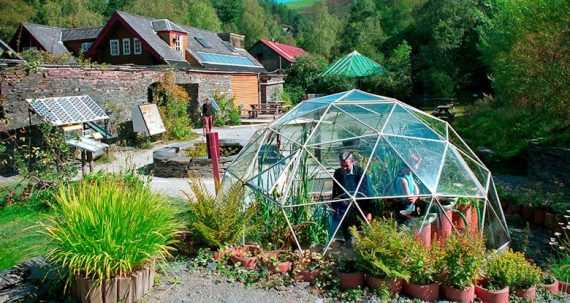

Paul and CAT, The Centre for Alternative Technology in Wales.

My name is Paul Allen. I’m an electrical engineer by training. And in 1988, I left Liverpool and came to work at the Centre for Alternative Technology in XXX in XXX quarry, and I’ve worked here now for 30 years doing A whole range of different jobs.

The Centre for Alternative Technology was set up in the early seventies to help rethink the role of technology for society to make technology work better for citizens, but within the limits of the planet. So, we began experiments with a live lab with a real living inside community, looking at how we provide food, how we deal with waste, how we make the lights come on, in different ways, to try and make them more resilient, done in ways that the people living with them better understand them, and to reduce our ecological impact.

Paul Allen from the Centre for Alternative Technology in Wales.

Well back then what was being talked about by the alternative movement was very far from the mainstream thinking. But it was at the cutting edge. And part of it was to have a holistic approach not just to focus on electricity or heat but to think about land use to think about food production to think about composting and waste and how all of those different systems can intersect as well. So that thinking has progressed over 45 nearly 50 years at CAT.

And now increasingly it’s moving into the mainstream, and becoming law, because the mainstream understands the physical limits of the world but also how to build better value better returns for human beings in return for what they’re looking for.

We have to recognise now we are in a climate emergency. We don’t have the option of business as usual for another 15 or 20 years. Now is the time.

So that’s the sort of thing I would suggest that process that needs to go through in all of business and industry almost to light a little candle as the voice of the future generations around the boardroom. Are we really behaving in the way that we need to, to respond to where we actually are in terms of human beings providing for the needs on earth.

Centre for Alternative Technology

Machynlleth, Wales, U.K

What is your company’s mind-print?

I think Corporate Social Responsibility means looking at the – not just the footprint of the business but also the ‘mind-print’ of the business. Looking at me the marketing and the advertising and how that affects social values and the idea of associating to be a successful family or to be an attractive male you have to have a big car, is something that really needs to be challenged, and something in the car industry needs to take responsibility for, because people do need personal mobility, because we want to take the kids to see grandmother. But there’s ways of doing that with buying the service, and having a car when you need it, rather than owning one, that can foster reliable cars, that are designed to last longer, where that sort of resilience and longevity actually helps the business model, rather than designing short life cars that are far bigger and heavier than they need to be. But backing up that huge amounts of merchandising and advertising and product placement.

So we need to challenge those norms.

Transport as an example

The Welsh government is supporting people who use transport, public transport, there is a free bus passes the road and on Saturdays and Sundays, to encourage more people to think about public transport.

We’ve also reached a point in terms of data harvesting where anybody in any town or county can put up a map where everybody puts the journey they want to do so that the local transport providers know who needs to travel where and when and what time so we can develop public transport systems that meet the needs of the citizens.

We’re not talking about delivering a utopia. We’re talking about just changing the infrastructure system, so human beings can continue to evolve within a safe platform, for the next two three four five hundred years.

Technology has to work within a plan that works and is driven by and has social license from citizens. We can’t have citizens lifestyle driven by what works for technology and the profit of corporate interest. And that’s the sort of shift in understanding that I think needs to really get out there.

Good practice

There is an enormous amount of really exciting really good practice happening.

I’d recommend you have a little look at the Ashton award winners’ website. Yeah with some really good videos and fabulous projects that are really happening on the ground now we just need to be like bees and cross fertilise cross pollinate these projects and help other people find them.

Basically, the problem we face is carbon lock-in, how we deliver housing, transport, food, lightbulbs coming on, that has co-evolved with fossil fuels over hundreds of years, well 150 years at least. So, we need to challenge those complex intertwined relationships. One of the most exciting ways that we see that is smart innovative community scale city scale projects.

One example is something like energy local where if you’re running a community hydro you don’t sell your electricity to the grid at 5:00 being in the house next door buys it at 15 even if they’ve got a virtual private wire network set up where people around the community hydro can buy the electricity cheaper and the hydro gets a better price for it and it builds relationships with citizens.

Or another good example might be at municipal level where Nottingham was running a project called Robin Hood energy. And essentially, it’s run by the Council for the people, buy and sell electricity as affordable as possible to bring the price down and citizens of Nottingham That’s an example of doing things for municipal benefits not for profit.

There’s so much good stuff out there and it is beginning to grow. The trick is to cross fertilise it so everybody can find out and access the really good ideas so we’re not all starting from the beginning.

There’s been technological advances in energy storage but there’s also been big advances in restorative agriculture and rethinking how we can revitalise natural systems to increase their carbon capture as well as improving resilience and soil quality.

I think one of the biggest challenges we face in rising to the climate emergency challenge is the people who are thinking about the solutions are quite often in their own individual silos of expertise.

There are so many core benefits in thinking about energy, food, transport, buildings, together in a single scenario. It also means that very, very big systemic changes as well.

We need to think about how we are supporting land use, what we’re using land for, drawing upon our indigenous wisdom of tradition.

Because if we look back at farms in Wales or in Scotland or in England over 30 40 50 100 years we can find fabulous records of how we used to farm with more cereals more crops more oats more turnips more vegetables and we can draw upon the wisdom not to go back in time but to rethink farm use in the 21st century in a way that helps us understand what the land is produced in the past and can produce in the future so that we can begin to produce a more healthy mix of food for better matches what human beings need to eat whilst also restoring soil quantity quality, and thinking about resilience because we live in turbulent times this turbulent climate turns into turbulent political times and having more resilience built into the system and more local connections and stronger skills verses that are more flexible can help give us a better system to pass over to future generations.

A shift in mindset

Well I think it’s very important to look at the history of seeing ourselves as part of nature. We are nature protecting ourselves rather than we are environmentalists protecting something that’s out there called nature that is nothing to do with us.

Nature provides for all of our lives, the oxygen provides food provide everything that we need. We are part of it. We are part of each other. And that shift is seeing interconnection I think is fundamental in helping change the behaviours that we need to see but also making us happier healthier human beings.

And partly I think there’s cultural norms that need to be rethought the idea that peasants work on the land and people who work on the land are poor and people who work in the urban environment are rich successful people, doesn’t really work out. If you look at how people’s happiness is measured people’s happiness is directly related to their connections with nature and the sense of meaning in nature. And then they feel that what they’re actually doing as social and natural worth rather than just churning out money.

———————————————————-

YUAN PAN

Yuan Pan Intro

Hello, everyone. I’m Yuan Pan. And I work with Professor Bhaskar Vira here at the Cambridge Conservation Institute on Natural Capital, particularly incorporating biodiversity into Natural Capital accounts.

Personally, I’m quite a pessimistic person, but when it comes to conservation, thought science, I think we are all quite optimistic. I think most of us are optimistic.

What is Natural Capital?

Natural Capital essentially is an economic term. So Natural Capital is the stock of the world’s natural resources.

The way I see it is a different way of framing the narrative of protecting nature. A story that will hopefully impact with policymakers and businesses. What we’re trying to say is that nature has value towards human society.

And some of that can be economic value, but it can also be other types of body as well. So within this research, we are only focussing on Natural Capital. But of course, I know about human capital and social capital. We’re also concerned with other types of value, like cultural values and kind of the intrinsic value of nature. Nature has value in itself, regardless of whether humans are here or not.

So Natural Capital definitely started out after ecosystem services emerged. So, people tend to use the two terms interchangeably nowadays. So ecosystem services are the benefits that we get from nature. So it’s like a flow of benefits. But Natural Capital is the stock.

And for a lot of businesses, they all doing ecosystem services, valuation or Natural Capital valuation. And I think that’s helping them to highlight that nature is kind of providing a lot of resources for them and they need to keep a resilient, sustainable ecosystem. Otherwise, for all businesses, they have raw materials.

Why take an anthropocentric view?

Stocks will eventually collapse. Basically. I would say essentially the terms are Anthropocentric, so they are human based. Because the definition for both of them is are benefiting human society. But what I have found in my research is that in fact, by using these kind of terms, you’re resonating more with businesses and policy makers, because unfortunately, we do live in a society where most people just concentrate on economic returns. Monetary values and these kinds of terms.

When you talk to businesses, their eyes tend to light up. And the kind of conservation that I did before, a lot businesses, they just tend to shy away from that, I think.

Biodiversity is a very difficult topic within Natural Capital accounting, and my project is trying to incorporate biodiversity in so currently lots of people just ignore biodiversity. And I think part of the reason is even as an ecologist, it’s very hard when I say like, what do you think when I say biodiversity? It can mean a lot of different things, trying to improve the situation with incorporating biodiversity by saying that it does have a lot of value, but the values are hard to measure because it’s the relationships are non-linear and also, they can’t be very easily monetary valued.

Everyone’s hearing this situation about the bees disappearing. And one of the things that people do pick up on when they talk about Natural Capital or ecosystem services is that these are very vital for pollination. But when you look at the research, but we can’t predict what will happen in the future with climate change and with the extreme weather conditions. So, in the future, we might need those other species that currently don’t seem to be performing any functions. But this is the other issue we’ve been talking about that for climate change. There’s, you know, kind of a very specific protection goal like either 1 degree or 2 degrees. And Paul, the reason that I think there’s been more focus on climate change compared to biodiversity protection per say is because climate change is quite easy to conceptualise.

Basically, you have a degree goal that you’re working towards. We can’t we don’t have a very specific protection goal.

Biodiversity objectives?

So, the first question is how much biodiversity do we need to sustain basic functions and processes that we don’t die as a society? But the second question is how much biodiversity do we want? And that’s not necessarily the same. A lot of people would like a very specific protection goal for biodiversity protection, just like climate change is very difficult to actually arrive a threshold value to say how much is it we actually want to protect?

We have a lot research and we have a lot of data, but perhaps there’s no kind of overarching narrative or kind of story that are linking them all together. I mean, currently there are papers regarding that. We need this kind of overarching objective. I don’t know whether you’ve heard of it. This thing called half earth or nature needs half.

It’s a very kind of bold objective that says that we should set aside half of earth for nature.

Basically, I can see that is good to have kind of an overarching, very easy to understand objective.

Functional Traits

I acknowledge the benefits of economic valuation and I have done some projects I’m done. But as an ecologist, I know there’s a lot of things that can’t be valued economically. And one of the things people have been looking into is kind of Functional Traits for like soil, like earthworms, etc. soil organisms or macro invertebrates in the river. I was interested previously in looking at Functional Traits, so people traditionally look at species as an ecologist. So how many species there is an ecosystem. But what people have been finding ecology is that Functional Traits are important to their body size.

Are they decomposing or what kind of specific thing the insect does in decomposition? And the research has been suggesting that we should be more concerned when a whole functional group goes extinct because then the services can’t be provided.

A case study for Nature Protection.

I’ve got a small case study, obviously, in China. So the lake system I worked on in China. It’s the third largest freshwater lake in China. There’s about four or five major cities around the lake. And what happened was there was so much pollution and urbanisation going around the lake that in 2007, people in one city had no access to tap water for about four or five days because there was a blue green algae bloom, basically that the lake constantly has been growing algae bloom. And it was only then I think the government realised that this is a really serious issue because they had to provide bottled water to the community for about four or five days. There was price inflation in the supermarkets and bottled water. And then they had to get people to clean the decomposing algae in the lake as well. So the whole massive event cost them, I think, billions of dollars to actually clean up.

And what some of the scientists later suggested is part of the reason could have been because a lot of the wetlands were reclaimed around the lake and the wetlands were destroyed. And if the wetlands had still remained as a buffer system for taking the pollutants out, then perhaps they wouldn’t have spent so much money trying to mitigate the risk after it happened. So I think with companies as well, they are looking at how do we prevent the risk from happening rather than let it happen. And then it will cost us a lot of money to actually repair the damage that’s been done.

Nature Capitals, Intrinsic Value and Relational Value.

As a researcher I am suggesting there’s multiple forms of value and not just economic value. And I think in terms of changing people’s perspectives or businesses or policy makers, I don’t think necessarily monetary valuation of either Natural Capital ecosystem services is going to do it. I think there has to be like a change in people’s values and opinions like inherent to the media. We’re trying to, I will say, improved a framework of Natural Capital concepts. So Natural Capital essentially, I think the value that’s coming out from there is instrumental value, basically kind of physical values. We can understand like providing water, providing food, etc. But there is also, like I said, with the intrinsic value.

So biodiversity I think has intrinsic value. You know, despite whether we are here or not that it does have a type of value. And lastly, which is this new type of value which is coming up, is called relational values. So how humans relate with nature and kind of how we make decisions about nature, either from kind of a moral or ethical perspective, regardless of whether nature has economic value.

This kind of moral, ethical imperative to protect nature. I think sometimes it does apply to even businesses. So a lot of businesses, they kind of want to have a good image and part of that good image is kind of doing environmental sustainability work. So that’s why I think Natural Capital, an eco-system services colony, is resonating quite heavily with a lot of the business sectors. As a traditional ecologist, I got into this because I love nature, but obviously working in China, I can see that the traditional approach was not working. A lot of businesses, they might not want to deal with biodiversity because even for scientists, it’s quite a complex concept.

Expanding the definition of sustainable business.

We need to work out a way that they need to be aware that biodiversity is important for their sustainable business. Previously, I did work with our local ecological knowledge in China, and the research kind of proved that we had a lot of experts going out to a remote region trying to find an endangered species and we couldn’t find them.

But I interviewed a lot of the ethnic minorities around there and they said, oh, we saw that species like two weeks ago in that river. And they helped me to map out where they’d seen the species. And it helped us to find the species.

Basically, there was a lot of different subject areas and research that needs to be done. That includes not only natural scientists, bills, shows from scientists, economists, accountants, even philosophers, so….

Connectivity to and in Nature

So obviously, you know, as a young ecologist to many years ago, my lecturers, you know, taught about kind of connectivity within the landscape. There is no point in setting aside, you know, national parks or no go zones if there is no connectivity, no corridors between them. This kind of threshold values that they having set for both of us. The I mean, there has been one which is January kind of 11 percent told percent of terrestrial errors should be protected as national parks, but actually the 10, even a 10 or 11 percent one.

It wasn’t based on scientific evidence. It was based on many years ago it in America. They decided that was this on sounded like a good number to protect national parks. And I think the current scientific evidence is showing that, you know, even like eleven percent, which we’re not hitting anyway in some areas is probably not enough.

Have some way that moved onto the half of kind of hypothesis, the kind of idea.

I think urban ecology is also a very important research area and that you can only consider the ones at national parks, but also the fact with urbanisation that people are losing their connectivity to nature. So even if we end up protecting everything in the national parks. But if everything is so urbanised, then children are not you know, they’re not exposed to nature. They’re losing connectivity to nature. They just like playing computer games. And they don’t see the point in protecting nature. I think in the future, it still won’t work.

END

———————————————————-

SOUND BRIDGE

PAUL JEPSON

Paul Intro.

Yeah, hi, so my name’s Paul Jepson. I’ve been a conservationist all my life.

I’m currently working for a progressive consultancy called Eco Solis and I moved into the enterprise sector just recently, actually after 12 years directing Masters’ courses in the School of Geography at Oxford University.

Prior to that, I was a practitioner working for birdlife in Indonesia and I started my career in urban conservation in Manchester and Shrewsbury in the UK.

Paul Jepson.

Enterprise and conservation.

We now realise that there’s a big role for enterprise in rewilding, landscape restoration. There’s a new area which I’m involved in, which we’re developing, which is working at the intersection of landscape recovery, technology and finance. The configuration of conservation environmentalism does need to change. But if you all work together, you’re more than the sum of the parts.

Really, if we can have change, we need to, you know, increase employment market, if you like. That’s not happening with NGOs, but with technology and actually more distributed organisational types and ways of working. There’s a real opportunity for free enterprise there. We can work for in an entrepreneurial way, for nature, in the environment, in many different sectors.

And for me, the future and the influence comes from informal networks connecting different organisational types in different sectors, working with clients. It’s really looking at code, designing solutions with them, bringing the creative thinking which is encapsulated within rewilding into those conversations.

On Rewilding.

There’s a number of different ways of thinking about rewilding. I mean, my favourite is that it’s just it’s just a label, a label like maybe the labels hippie or punk or whatever, which signify an unsettling sort of reassessment of where we are, maybe a desire to shape up the future. But rewilding is doing that in terms of how we think about nature conservation, our relationship with the environment and so forth.

So, one way of thinking about it is just that new opportunity for people to engage and shape futures, shape futures of nature, the environment, our engagement with it. This is talking a little bit from a Western European perspective, but a lot of our nature conservation has been focussed on protecting conserving benchmark ecosystems or habitats as particular assemblages of plants, specific types of woodlands or grasslands or so forth. Or it’s been about protecting declining species and so forth.

A lot of it has been focussed on elements, units of nature and particular identities of nature. It’s enabled strong law, clear policy targets, management targets and so forth. I think this particularly long term ecology and the advances in that science, which have been enabled by technology, we’ve come to understand past ecosystems much better and come to understand that across much of the world, including Western Europe, grasslands and large herbivore assemblages or mixed wood pastures were the norm and they supported huge diversity and had great resilience and all of these sort of things.

But actually millennia ago, humans wiped out a lot of the big megafauna or we domesticated it. That actually we’ve been living in a world where we’ve internalised ecological impoverishment, both in our culture and in our institutions and in our conservation policy.

There isn’t one nature. There isn’t a pristine nature that there’s multiple past natures. What would happen if, to the extent we can we reassemble in Europe, the large herbivore assemblies?

So things which have been divided like, you know, we only know cattle and horses in the domestic livestock farming. We still have deer in the wild realm. What happens if we just reassembled them all together? There were some very pioneering experiments of this in the Netherlands.

It was quite extraordinary what is happening when this idea of rewilding is put into play. Amazing kickbacks of a nature rebounds at nature habitats on smaller ecosystems like freshwater ecosystems appearing in places which we never knew them. Species which we thought were rare, suddenly returning in abundance and much more dynamic natures. That’s the sort of scientific conservation identity of rewilding.

Us v European versions

And I suppose when we say, well, what does rewilding mean? It means different things to different people. The term originated in North America and there rewilding was much more tied up with concepts of wilderness and maybe Christianity and bring wolves back and top down trophic cascades in Western Europe.

The version of rewilding which I’m involved in is a very pragmatic version which says actually if we’re recovering and restoring nature, we can’t go backwards. We can only go forward so that the rewilding natures that emerge will be different from anything we’ve ever known before. But they’ll be equally as wonderful as nature before. But if we are shaping nature, we can actually shape those natures to solve current problems.

So there’s a very sort of integrated form of rewilding emerging in continental Europe. For instance, on the Dutch Delta, with climate change, there’s increased rain events, pulses of water coming down these huge rivers. But by taking out some dikes, buying a public cultural land a very pragmatic way, using the silt that brick building to re restore these sort of natural river braiding and channelling, bringing in natural grazing. So bringing in herds of of wild eyed horses, cattle, the introducing beavers, again, recreating those large mammal assemblies in these areas, you’re getting incredible nature. But cities and companies have been benefiting from lower flood management and insurance costs. The construction industry benefited from having a source of bricks. People have benefited from just having great areas where you can go and hang out and have a nice time at weekends. And then there’s tertiary tourism economies building of that. So you get these really lovely, neat systems starting to emerge.

Another example of a nature-based solution with rewilding is pragmatic. European version would be based in Portugal.

The kind of climate change adaptation at the centre of the IBM venture is getting drier. There’s rural the population, which is a loss of traditional herding. This is increasing biomass.

That’s leading to intensity of wildfires, which my goodness, what a problem.

But actually doing rewilding and bringing in natural grazing again, you reduce biomass load, so you induce the intensity of wildfires and then you get you can either use them as natural areas for tourism and sort of wilderness type areas or you could do sort of new pastoralist type economies on it. So that’s what distinguishes us as a species on this planet, is the fact that we have this third reality where a lot of what we do and how we act and how we think is shaped by narratives and stories and language and so forth. And many of these narratives, they, you know, they develop over time, they sediments over time, but they really do shape how we think and how we are, how we move ahead and how we relate to each other, of course.

Across the world we are seeing an increasing amount of wildfire outbreaks fuelled on by global warming, biodiversity collapse and climate unpredictability.

Emerging narratives

So I think it’s important we develop a narrative of nature and our relationship with environment, which was a really powerful narrative and it’s achieved much. But it actually is a very cautious and protectionist narrative such that we all sort of wanted to put nature out there and separate and fragile, maybe people who colleagues in other sectors, architecture, urban development, industry or whatever, they haven’t really seen nature as a force which we can engage with to shape futures or shape place based futures. It’s almost saying something is a bit less under threat. We need to put it aside or whatever in rewilding.

We’re seeing a different narrative emerging there that that narrative of empowerment. This is where we’re at. We can’t go back. There’s not a lot point in blaming people. Let’s just stop doing something to make things better. And then there’s narrative elements.

They often talk about pioneer action or people getting together and and through this, starting to reassess how we might do things. Values, world-views and bringing people on board and this sort of momentum.

So, much more of an interactive narrative from which emerges stories of of wellness, I suppose so adaptation, a word which comes to my mind, which you heard, is this notion of offsetting. You know, we offset harm, so companies do that. You know, they’re offsetting their carbon footprint. They’re doing biodiversity offsets. And that’s one way to do it, saying, well, OK. You know, we just feel a bit bad about things. So we’ll we’ll try and offset our impact elsewhere. OK, fine. But again, it’s not saying, well, you know what, I don’t want to feel bad for it. I want to be contribute to a vision and I want to be part of change. Many. Know. I think that’s what many people want.

A narrative of recovery

I woke up one morning. It’s a narrative of recovery. Just was in my head at my breakfast, quickly jumped on my bike, was down into the university and got onto the academic search engines and just started pushing narrative of recovery in two web of science and outputs.

This I mean, a massive amount of literature, but these papers are mental health recovery.

The crucial thing which really grappling me in the link between these narratives and the narratives I was hearing in in rewilding or this new environmentalism is rather than pressuring others to act on our behalf, which is part of the classic campaigning thing of environmentalism.

It was really like, you know, you can’t wait for a national health service or the doctors to sort yourself out. Just sooner or later, you’ve got to start taking responsibility for your own health. And that’s the always the epiphany people have.

And then you start engaging, you start acting, you start beginning just getting together and starting to make projects happen and finding that that new way, that wellness, that recovery in it. So it’s really interesting the term rewilding and how is the original ideas were more associated with classic sort of U.S. wilderness ideas. These ideas in Holland started under the term nature development, which was a sort of technocratic policy, and then the term rewilding has been applied to them all.

Now we talk about semantics, the re prefix. It can either, you know, its Latin origins, it can either mean back or again. And that’s really interesting, that difference. So, what we’re finding is that some people immediately see it as going back, you know, going back to a sort of more wilderness fortress conservation way outside, people telling people what to do.

But actually in this European one, it is really using the rivers again. So, we can re-find engagements with nature, connections with nature.

And it’s really interesting when you look at all of the reworks which the European rewilding seems to align with. So you could say that the way we use urban regeneration, regenerating urban areas is nothing like, you know, you don’t go backwards. It’s always going forward. They look quite different. The recovery, in a sense, you recover a song about injury. You might not ever be the same again, but you recover. How do we think about recovering Earth’s systems, of which we are part of it is the big international agreements and policies, but part of it is just as people getting going on things in their areas, in their competencies, in their places and through that getting this sort of bottom up momentum. We are friendly to the natural asset framework.

Nature Capital or Assets?

For me, capital is quite a linear type of thinking, often capitals. We think about capitals and then they can create flows, you know, so whether it be labour money or natural resources can be an input into a production service.

And sometimes it’s a bit divisive as well. And it sort of gives prominence or pre-eminence to economic logics, whereas assets and assets are actually a lot more meaningful.

I think to people. So, example I use is with culture, with human assets, with infrastructural assets, with institutional assets, and that’s what creates a natural asset. And some of those assets are already here. But we can’t think about restoring recovery and creating new natural assets and new natural assets which are part of that place. Building or place, rejuvenation, regeneration, whatever we whatever we want to call it.

You know, one of these nice things about the rewilding logic, it sort of releases you from baselines. You take inspiration from past nations to shape future natures.

You’re not trying to recreate something so that they create space for different groups to come together and to think about what forms of natural asset they may want and where those natural assets may be. I’ll give the example in the Netherlands that they needed new natural assets along their rivers to adapt to climate change or whatever. It might be in other areas that people are looking for new natural assets to have somewhere to go. Dog walking, which is quite popular in the UK or have somewhere to have a wild experience, somewhere which produces food in a more a healthier and more ethical way.

A dream project

I think the dream client is somebody who had or could create some space where you could do something pioneering contained areas where you’re doing something new, where you’re experimenting, just trying out things new. And people can come and talk about them. They can bring in people who are sort of more progressive, change agent can get involved in them.

They can be used as exemplars for adoption in wider society. I’m talking about innovation hubs, the nature.

A dialogue way, a code design way of changing and bringing about new environmental or new natural futures.

Pioneer demonstration, experimental projects approach. I think it’s a good way of yeah, co design. I think that’s the word co-production of Environmental Futures. With outlined a set of rewilding principles, so sort of guiding principles which aren’t prescriptive but very sort of characterise what rewilding is, so the fundamental of restoring ecological dynamics and processes, taking inspirations from past natures to shoot showed the futures working with restored forces of nature.

A strong sense of place

One of the things we do know from, you know, from theory Anderson’s imagined communities is that nature that nature is very good at place branding and given the sense of nature and this sense of territory and sense of community and belonging.

One of the interesting things is that if their novel, the new natures, which we’re creating, which they are, if we’re reassembling our church for and biotic diamonds. So if they’re not protected by nature conservation legislation because they don’t fit with that. So, you know, the more they become these free spaces and actually you can be much more relaxed about what people do in them. And again, this is happening in the Netherlands, where, if you like the most famous site, gather support. People are allowed just to do whatever they want in it. And of course, the interesting thing is because it’s dynamic and wild and this big stuff walking around. Most people tend to keep to the path. You become human again, you know, so like a bit scared. Nobody is telling you what to do. And if you want to go off. I mean, I did this once. If you want to go in and go off off the footpath and go in and get dirty, look for beavers and have a bit of an adventure, you can do it. But there’s very few people who do that.

We’re in an increasingly regulated society. Whatever the merits of it, there’s much more health and safety, we’re told, to look after ourselves as.

All of this, the opportunity just to get out into natural areas in your town where you can just do what you want. Social norms, rules and regulations. I mean, that that sounds to me to be valuable. It is an interesting thing about nature is that once you start helping it recover, it says thanks so fast.

Nature does have a force.

From anxiety to solutions.

In the 1990s, I worked in Indonesia and I set up the BirdLife International Program there, and for the first part I was working out in eastern Indonesia on parrot conservation, so forth. But then actually after I left that job, I started working as a consultants, mostly with the World Bank and a couple of NGO on on the Sumatran frontier.

And it was a pretty hard time in some mice that, well, two or three things were going on. Really? What one is, you know, you go to a forest area and you go six and play later. And the landscape was totally, totally trashed.

And a in almost turn down these roads, the roads and as swampy areas with just the skeletons of trees stood out.

There a bit harrowing, actually, I realise I mean, at the time I was sort of in this professional, I, you know, doing this sort of way, but it was getting to me partly maybe also got to me because I had such magical times in my backpacker days and tropical rainforests just feeling the aesthetic and the sheer beauty of it and the wonder of it.

You know, just feeling that’s been lost and been lost for it’s the frontier.

But then the other thing which really got me was to other things, really. One was the chaos international NGOs working at ministerial level, World Bank.

And this realisation that we had no control over the chaos of the frontier, just out of control. Big NGO sort of dropping off the real active engagement with the ground.

Well, I listened a bit to Radiohead, but I actually listened to okay, computer and sorted out. You should listen to this. And it just became the soundtrack of my life. And anybody who knows the okay computer algorithm will just know sort of wailing crescendos and then these really rock-hard guitar riffs. And it just became the soundtrack of my life. I think it’s going to be honest. I realise that that period I was I moved into a place where teaching the students then started talking back to us, not just me as selectors and say, look, we don’t want to hear all of this.

You know, all the evidence about the decline of nature and biodiversity loss and blah, blah. You know, we know things were in a bad way. We don’t want to be a future where we’re just defending the inevitable. And, you know, these images are smashing M.E. mind. You know, we want theory, ideas and learning so we can shape the future. And then as part of that, I started looking outwards and I found the work going on in the Netherlands and I started taking field trips out there and then came into this. It doesn’t all have to be like the Sumatran frontier.

Even though we may trash things, there is still opportunities for nature to recover and to work on nature recovery.

END

———————————————————-

SOUND BRIDGE

CREDITS

Tanya: Thank you for listening to this episode of Nordic By Nature, ON NARRATIVES. You can find more info on our guests and a transcript of this podcast on imaginarylife.net/podcast

Nordic by Nature is an Imaginary Life production. The music and sound have been arranged by Diego Losa. You can find Diego on diegolosa.blogspot.com.

Many thanks to our guests. You can find Tom Crompton on commoncausefoundation.org.

Paul Allen is at the Centre for Alternative Technology, on cat.org.uk.

Your can contact Dr. Yuan Pan’s through the Geography department at Cambridge university in the U.K. Her research into Natural Capital was with Professor Bhaskar Vira at The Cambridge conservation initiative. Please see cambridgeconservation.org. or contact the Natural Capital hub for more information into Natural Capital as well as organisation and company toolkits

Paul Jepson is currently Nature Recovery Lead at the consultancy Ecosulis. Their website is Ecosulis.co.uk.

You can contact Ajay Rastogi via foundnature.org where you can read about the Foundation for the Contemplation of Nature. You can also follow the Foundation on Facebook, and on Contemplation of Nature on Instagram.

Please help us by sharing a link to this episode with the hashtag #tracesofnorth and follow us on Instagram @nordicbynaturepodcast. We are also fundraising for a new series of podcasts on panteon.com/nordicbynature.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on our podcast. Please email me, Tanya, on nordicbynature@gmail.com

END