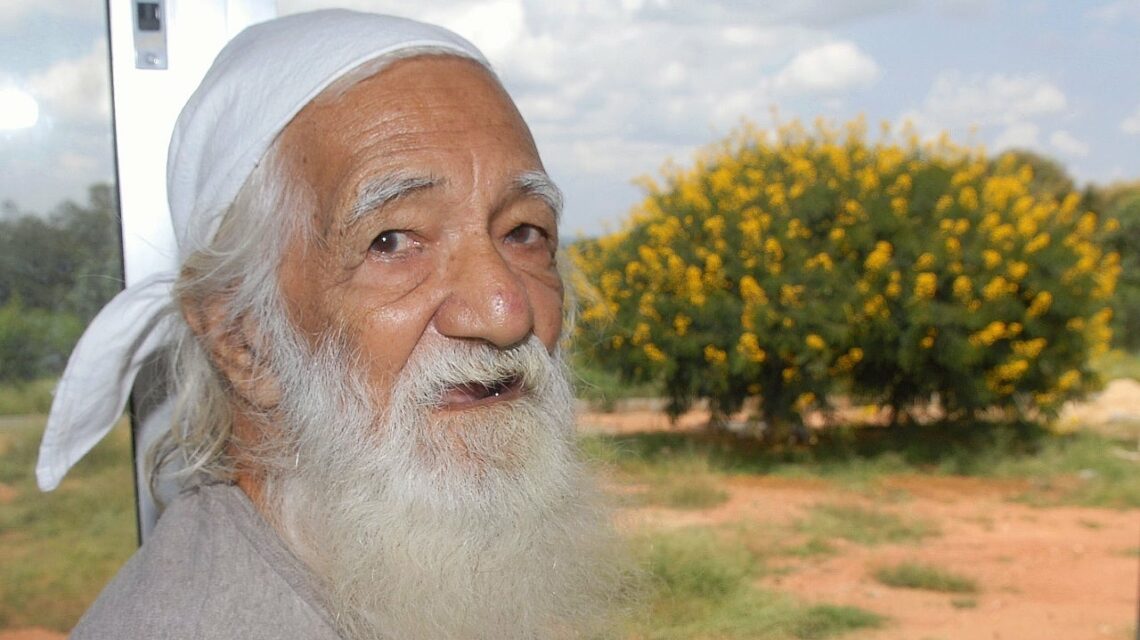

Clad in a white Khadi Kurta Pajama, a distinguished man with a long flowing beard was on indefinite fast on the bank of Bhagirathi in 1994. He was fasting to demand a thorough review of Tehri Dam project. It was Sunderlal Bahuguna. Sunderlal Bahuguna (9 January 1927 – 21 May 2021) was an Indian environmentalist and Chipko movement leader. The idea of the Chipko movement was his wife’s- the original ‘treehuggers’. Suderlal fought for the preservation of forests in the Himalayas, first as a member of the Chipko movement in the 1970’s, and later spearheaded the anti-Tehri Dam movement from the 1980’s to early 2004. Sunderlal was influenced by Gandhi and lived most of his life as an activist serving social and environmental causes.

It was already the 34th day and the news was spreading fast. I was working at an environmental organization in Delhi when the youth network INTACH was mobilizing people to go to Tehri with Medha Patkar-ji, the leader of Narmada Bachao Andolan. Almost 30 of us took the night bus to Tehri with her.

It was amazing to see Sunderlal-ji’s vigor and energy as he filled us with ecological, geological, cultural, social, historical, economical and spiritual insights into why the Tehri Dam should not be built the way it was conceived and planned.

Having studied environmental science in college when the EPA (Environmental Protection Act, 1986) had just come out; I could feel that the explanations Sunder Lal-ji gave were much more comprehensive than any scholarly literature could provide at that time.

Filled with awe and inspiration, we sat through the night on the river bank and spent another couple of days witnessing Sunderlal-ji’s. practice; his prayers, his deep-seated belief in human goodness, his natural curiosity and universal values of human dignity and sovereignty.

This was the first time I felt in depth how limited our university education is. It gives us the impression that ‘knowledge’ is incubated in separate silos.

Obviously, the EIA (Environment Impact Assessment Guidelines, 1988) that came as a follow up to EPA were far too removed from the complexity that Sunder Lal-ji talked about.

My young environmental activist’s restless heart was further unsettled…my life in Delhi felt futile. I requested for a job somewhere far and remote, and fortunately, my office was starting a Ajay Rastogi programme in Arunachal Pradesh.

So, soon enough my wife and I were living in Itanagar. As the luck would have it, the Arunachal unit of Himalaya Sewa Sangh, part of a network of the Gandhian institutions, was close by. Many Gandhians from across the country had gathered for an annual convention.

There we met more women and men who wore simple khadi clothes and knew much more about their place than others, whether it be about water resources, forests, weaving clothes, rearing honeybees or raising cattle and growing crops.

They wore ordinary chappals, talked in the local lingua-franca mix of languages, laughed a lot and ate simple meals. They didn’t have any airs about the Padma Shri/Padma Vibhushan awards even though several of them were national awardees. The prestige seemed only incidental unlike our graduate events where we are instilled with a kind of hubris that now we know how to change the world.

Many times, the accessories to our work become more important to us than it should: proper shoes, dress codes, computers, phones, office etiquettes and the like. These people just went around in ordinary sandals/chappals with humility. They were easy to access and learning from them was natural, their eagerness to share life experiences with laughter was another dose of reform that perhaps we need in the echelons of educational institutions. It reminded me that university degrees are sometimes are treated with more respect than the humane aspect of practical wisdom.

Having settled down in Arunachal, it was time to reach out to the local communities and start working with them. My first encounter was with an Apatani farmer. She was in her paddy field selectively removing some plants of specific age and within the same species of weeds.

Prior to studying Environmental sciences, I had graduated from a degree in Agriculture and my immediate instinct was to share what I had be taught with her. She should keep the whole field clean, devoid of anything but open paddy.

However, with the language barrier between us, I was forced to be patient and observe. It was only after we reached the Kasturba Ashram in Zero, that I could raise the question to a a Hindi speaking sister, who was also simply clad in a white khadi saree.

The womens’ explanation was vivid with details of the many uses that those so-called ‘weed’ plants have, not just as food for humans, but in harbouring and nourishing other species that in turn are nurturing creatures up the food chain all the way to fish and to birds of prey. They were explaining ‘companion planting’ to me in a much broader and more integrated way. Not only did she think about her crops, she thought about the landscape’s systems.

I realised that she was not only a farmer, she was a steward of the local ecosystem. It was not just a lesson in landscape ecology or watershed science but an integrated theoretical lesson in agro-ecology that in the classroom would require modelling and experimentation on crop mixtures.

She had inherited the wisdom from previous generations and worked with a natural flare and grace. Her simple bamboo dwelling was perched on stilts. It recycled practically all the household water and food waste. No green labels or certificates, no ‘green products’ and no responsible business awards or carbon credits. Her life was simple but perfectly balanced and very rich.

In the agriculture degree I took 30 years ago I don’t remember taught indigenous knowledge systems or ‘bio-cultural agriculture’ at all, and when they were mentioned they weren’t spoken about respectfully. Though, there is some difference today, with acknowledgement for these and other organic systems, the mindset of care and stewardship is yet not a part of our natural resource education.

It isn’t just a matter of what we have to learn, there is so much to unlearn. What should we retain and how much do we have to reform in ourselves and our institutions? What is the shift in mindset we need to make? We need this type of deep questioning.

What we learn from indigenous practice is often dismissed as only relevant for small scale or “alternative” farming. 30 years on, I am not so convinced that what I was taught should be mainstream agriculture. I have had the fortune of meeting and learning from people who lived rich lives using traditional sustainable methods and who changed their life to ‘be the change’.

Sunderlal-ji left his body 2 weeks ago on May 21, 2021. He was the end of an era. He brought to us extraordinary accomplishments and changes through simplicity and the force of self-conviction. I hope his spirit remains and will help consolidate a new movement in future.

There are many more leaders like him who are able to bring about the kind of ‘transformative education’ in our institutions of learning that I hope for.

Today, I am fortunate to live in a village, close to Lakshmi Ashram in Kausani where Radha Bhatt lives. Radha is in her eighties but helping young girls flourish, despite her ailing health. It would be a real loss for the youth to not have had the experience of meeting and getting inspired from mentors like Radha Bhatt and others who are spread across in every community and country.

How many universities equip us to deal with local issues? How do they teach us to incorporate the local traditions and best practices that have evolved over generations? This type of indigenous knowledge has positive potential in pretty much every subject.

How many agricultural scientists are able to break through the silos to make a self-regenerative paddy field and see it and ourselves as a part of the wider ecosystem?

Above all, are our institutions able to redefine the pursuit of happiness by instilling pride in the deep wisdom, love, compassion and optimism kept alive through living a simple and rich everyday life?

Ajay Rastogi

Majkhali Village, Uttarakhand, India